My first reaction to the new rebranded packaging revealed by PepsiCo yesterday, that is to make its way onto store shelves by June 2021, was “Hey, why didn’t they keep the likeness of Aunt Jemima and honor Nancy Green by renaming the syrup and pancake mix after her.” Sounds like the ‘woke’ thing to do, that is until you go a little deeper into Aunt Jemima’s sordid past. Within minutes, you’ll agree that getting rid of this racist, human mascot imagery from their product was the only option, and you should actually be very angry when you think to yourself, why did it take so long?

The truth is that Aunt Jemima was not based on a real person, if that were the case, then the argument that the likeness should’ve been retained in the rebrand with a simple name change might have some validity. In fact, the opposite is true. Not only was it NOT based on a real person, it was based on a racist stereotype designed to dehumanize and depict African-Americans as passive servants, cooks and slaves.

Even when Quaker Oats bought the brand in 1925, they doubled down on stereotyping: they trademarked it. This human “trademark” became one of the longest running advertisement “mascots” in history.

One that would go on to be portrayed by different living women at least half a dozen times before it was decided it would be retired in the midst of civil unrest, demands for social justice and racial division

From a brand evolution perspective

- The latest package design are the “breadcrumb trails” to the previous packaging. We see that PepsiCo has chosen to retain the package colors, the shape, the typography (slightly updated) and the classic pancake imagery is almost identical to the previous versions.

- Whenever you rebrand, and in this case, a full on name change (finally!) ‘hand-holding’ with a graphic that spells out the ‘previously known as’ moniker is a highly effective tool. In time, that small reminder of “Aunt Jemima” will slowly fade away, but it’s there in this edition because it is a transitional phase of the rebranding process.

- I also suspect that PepsiCo wanted no part of keeping Aunt Jemima’s likeness alive in 2021, especially since the family of two of the women who portrayed her were actively seeking a large settlement.

- The name itself was what came first and what was most offensive to many of our African-American brothers and sisters. Once the name is gone, the likeness needs to go as well.

From a branding perspective, I support this move.

Above is the previous rendition of the Aunt Jemima logo with no head scarf, a white collared shirt and pearls was more of a brand refresh than a rebrand. It still featured the likeness and the name, which for many, remained derogatory and a relic of minstrel shows and mammies. It was last redesigned in 1989 and was recently retired in December of 2020. The new packaging will appear in stores in June of 2021.

A Timeline of the Brand History: https://www.auntjemima.com/our-history

Aunt Jemima’s Long Racist History in American Advertising

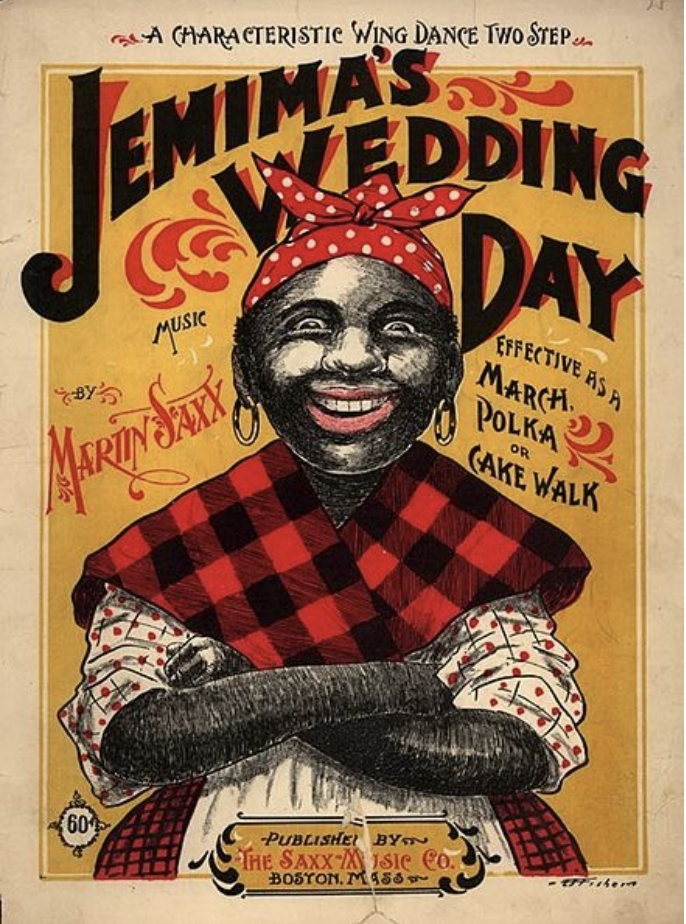

A depiction of a “Jemima” from 1899 – Aunt Jemima is based on the common enslaved “Mammy” archetype, a plump Black woman wearing a headscarf who is a devoted and submissive servant. 1

History: The origins of a Brand

“Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype,” the company admitted at the time. Indeed, the brand’s name and image were inspired by “Old Aunt Jemima,” a song and subservient mammy character popularized in minstrel shows during late 1800s.

“Pearl Milling Company was founded in 1888 in St. Joseph, Missouri, and was the originator of the iconic self-rising pancake mix that would later become known as Aunt Jemima,” Pepsico said in a press release.

PepsiCo subsidiary Quaker Oats, which last June pledged $5 million over the next five years to support the Black community, announced Tuesday it would contribute $1 million in Pearl Milling Company’s name towards a program designed to “empower and uplift Black girls and women.” **

**Source: Cleveland.com

Aunt Jemima Ads and her “Brand Evolution” Over the Years

Here are some sobering reminders of America’s advertising past in the form of Aunt Jemima Ads and her “Brand Evolution” Over the Years

Say Their Names: The Women Who Played Aunt Jemima

The following excerpts come from Wikipedia:

Nancy Green (Born enslaved on March 4, 1834 as Nancy Hayes) holds the distinction of being recognized as he “Advertising World’s First Living Trademark” (Human Mascot) when she was encouraged by the Walker family to respond to a search for a “Mammie” type advertising character to represent “Aunt Jemima” for the RT Davis Milling Company. Mrs Green had served for two generations of Walkers as Nanny, Nurse, Housekeeper and Cook at the time. She was almost 60 years old when she debuted as the face of “Aunt Jemima”

Agnes Moody When Nancy Green refused to travel across the Atlantic in 1900 to promote the Aunt Jemima brand at the Paris Expo, the RT Davis Milling Company replaced Ms Green with a ‘new’ human mascot to perpetuate the slave / minstrel character overseas. The second woman to portray Aunt Jemima was Agnes Moody who was already famous (locally) for being skilled in the kitchen with cornmeal. She went on to be paraded around the world as the “Original Aunt Jemima” for almost 40 years.

Anna Robinson Anna Robinson was hired to play Aunt Jemima at the 1933 Century of Progress Chicago World’s Fair.[1][2] Robinson answered an open audition, and her appearance was more like the “mammy” stereotype than the slender Nancy Green.[17] Born circa 1899, she was also from Kentucky and widowed (like Green), but in her 30s with 8 years of education.

Rosa Washington Riles Rosa Washington Riles became the third face on Aunt Jemima packaging in the 1930s, and continued until 1948. Rosa Washington was born in 1901 near Red Oak in Brown County, Ohio, one of several children of Robert and Julie (Holliday) Washington and a grand-daughter of George and Phoeba Washington.[51]

Anna Short Harrington Anna Short Harrington began her career as Aunt Jemima in 1935 and continued to play the role until 1954. She was born in 1897 in Marlboro County, South Carolina. The Short family lived on the Pegues Place plantation as sharecroppers.[54] In 1927, she moved to Syracuse, New York. Quaker Oats discovered her cooking pancakes at the 1935 New York State Fair.[55][56][57] Harrington died in Syracuse in 1955.

Lillian Richard was hired to portray Aunt Jemima in 1925, and remained in the role for 23 years. Richard was born in 1891, and grew up in the tiny community of Fouke 7 miles west of Hawkins in Wood County, Texas

Edith Wilson Edith Wilson became the face of Aunt Jemima on radio, television, and in personal appearances, from 1948 to 1966. Wilson was the first Aunt Jemima to appear in television commercials. She was born in 1896 in Louisville, Kentucky. Wilson was a classic blues singer and actress in Chicago, New York, and London. She appeared on radio in The Great Gildersleeve, on radio and television in Amos ‘n’ Andy, and on film in To Have and Have Not (1944). On March 31, 1981, she died in Chicago.[3][58]

Ethel Ernestine Harper Ethel Ernestine Harper portrayed Aunt Jemima during the 1950s.[3][27] Harper was born on September 17, 1903, in Greensboro, Alabama.[59] Prior to the Aunt Jemima role, Harper graduated from college at the age of 17, taught elementary school for 2 years, high school mathematics for 10 years, moved to New York City where she performed in The Hot Mikadoin 1939 and Harlem Cavalcade in 1942, then toured Europe during and after World War II as one of the Ginger Snaps. On March 31, 1979, she died in Morristown, New Jersey.[3][60]She was the last individual model for the character’s logo.[27]

Rosie Lee Moore Hall Rosie Lee Moore Hall portrayed Aunt Jemima from 1950 until her death in 1967. Hall was born on June 22, 1899, in Robertson County, Texas. She worked for Quaker Oats in the company’s Oklahoma advertising department until she answered their search for a new Aunt Jemima.

Aylene Lewis Aylene Lewis portrayed Aunt Jemima at the Disneyland Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House, a popular eating place at the park on New Orleans Street in Frontierland, from 1957 until her death in 1964. Lewis became well known posing for pictures with visitors and serving pancakes to dignitaries, such as Indian Prime Minister Nehru. She also developed a close relationship with Walt Disney.*

Closing Thoughts

Make no mistake, Aunt Jemima started out as a racist, minstrel character, and should have been dropped a very long time ago. It was not until our nation’s civil unrest, sparked by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police officers that PepsiCo decided to reconsider using this representation in their popular food products.

They continued to use the Aunt Jemima branding AFTER the families of Nancy Green and Anna Short Harrington both tried to unsuccessfully sue PepsiCo for lost wages and compensation. All I can say about this rebrand is that it’s about time and it’s never too late to begin moving in the right direction.